Registration Reciprocity

Exactly when conflicts surfaced between the District of Columbia and its neighboring states, especially (and perhaps exclusively) Maryland, due to the lack of motor vehicle registration reciprocity is unknown. Vehicles owned by residents of Maryland and Virginia were first required to be registered in those states in 1904 and 1906, respectively, so there were no reciprocity issues prior to the enactment of Maryland's first law in May 1904. In fact, we do not know whether reciprocity itself was the issue, for in published accounts that reference the subject, the topic more often seems to be the consistency and fervency with which traffic and vehicle registration laws were enforced rather than the registration laws themselves. In other words, we believe that motorists likely did not object to the lack of registration reciprocity nearly as much as they did what was perceived to be, and in fact may have been, inconsistent enforcement of vehicle-related laws based upon the jurisdiction(s) in which particular vehicles were based.

The few extant news reports and Automobile Board references about this subject focus on Maryland, presumably because of its numerous road crossings into the District as opposed to the limited number of ways to enter Virginia at the time. Therefore, Maryland is the focus of our attention.

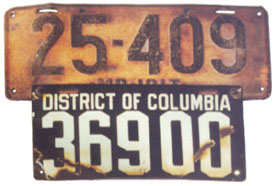

Throughout the United States from the time that vehicles were first required to be registered in adjoining jurisdictions (be they states, counties, or municipalities), registration reciprocity was presumably absent until some later date upon which officials from both localities reached an agreement to honor each other's registrations. Theoretically this could have occurred immediately upon the second jurisdiction's law taking effect, but more likely motorists that routinely crossed a specific boundary had to register their vehicles in both (or more than two, such as D.C., Md., and Va.) until a reciprocity agreement was reached. Evidence of this lack of reciprocity takes the form of photographs that show plates of more than one jurisdiction on the same vehicle (examples of which may be seen by clicking here), and in the region of our focus it was, in fact, unusual through 1924 to see a D.C-based car that did not also have a Maryland plate. (The modern equivalent gradually ended during the 1970s and early 1980s when a nationwide reciprocity agreement, the International Registration Plan (IRP), took effect, allowing operators of interstate trucking companies to register their vehicles in only one state. Previously, plates and permits of several states were routinely displayed on the front of many truck tractors. For more information, click here.)

Throughout the United States from the time that vehicles were first required to be registered in adjoining jurisdictions (be they states, counties, or municipalities), registration reciprocity was presumably absent until some later date upon which officials from both localities reached an agreement to honor each other's registrations. Theoretically this could have occurred immediately upon the second jurisdiction's law taking effect, but more likely motorists that routinely crossed a specific boundary had to register their vehicles in both (or more than two, such as D.C., Md., and Va.) until a reciprocity agreement was reached. Evidence of this lack of reciprocity takes the form of photographs that show plates of more than one jurisdiction on the same vehicle (examples of which may be seen by clicking here), and in the region of our focus it was, in fact, unusual through 1924 to see a D.C-based car that did not also have a Maryland plate. (The modern equivalent gradually ended during the 1970s and early 1980s when a nationwide reciprocity agreement, the International Registration Plan (IRP), took effect, allowing operators of interstate trucking companies to register their vehicles in only one state. Previously, plates and permits of several states were routinely displayed on the front of many truck tractors. For more information, click here.)

"Warfare" Between D.C. and Maryland by 1913

Because the District is surrounded on three sides by Maryland, that state's relevant laws and regulations are known to Washingtonians. Evidence to support this may be found in the Automobile Board's fiscal year 1904 annual report, written within six months after Maryland's first vehicle registration law was enacted, in which registration laws of the New England and Mid-Atlantic states, with the notable exception of Maryland, are abstracted in considerable detail. Of that state, Mr. H.M. Woodward, secretary of the Board, writes "The Maryland law is so well known to all owners and operators of motor vehicles in the District of Columbia that I have made no extract from it, other than this: 'That every resident of this State who is the owner of a motor vehicle, and every nonresident owner whose motor vehicle shall be driven in this State shall pay to the secretary of state a registration fee of $1 for each vehicle registered.'"

Although we don't know when the lack of reciprocity between D.C. and Maryland became particularly contentious, it could certainly be described that way by early 1913, by which time Maryland's registration fee had increased dramatically from the initial $1 fee of 1904. It appears that by 1913 Washington motorists were not only tired of paying between $5 and $25 annually to register their cars in Maryland, but they were also troubled by their perceived harrasment by traffic control officers in the Old Line State. Therefore, in January 1913, when there was no vehicle registration fee in D.C., a regulation was enacted that required non-resident motorists operating their vehicles in the District to pay to the Automobile Board a fee equal to the same registration fee that a D.C. resident would be required to pay in the motorist's home state if a D.C. motorist wished to drive there. This "January 1916 Provision" was replaced six months later with a related regulation that was easier to apply, the "July 21 provision," and both of these regulations are discussed in detail here.

The two 1913 non-resident registration provisions were enacted in order to stop what the Washington Post referred to in a January 1913 article, subtitled "Commissioners Plan to Stop War on Capital motorists," as "the warfare on District automobiles conducted in neighboring States." At the time, in contrast to the absence of registration and operator's license fees in D.C., Maryland motorists paid a $2 annual license fee and an annual vehicle registration fee of between $5 and $25, depending on the vehicle's rated horsepower. D.C. residents that wished to drive in Maryland also were required to pay these fees, of course, whereas it cost Maryland motorists only a one-time $1 plate fee for the privilege of driving in the District. The article indicates that only Maryland taxed D.C. residents in this manner, suggesting that D.C. residents operating their vehicles in Virginia apparently paid little or nothing for the privilege. According to the Post, it was hoped that the adoption of the January 1913 provision would "have the effect of making officials of nearby States, principally Maryland, more reasonable in their treatment of District motorists."

In writing that "So many protests about treatment accorded District automobilists in neighboring States have been made recently that definite action has been demanded," the Post references not only the registration fee disparity between D.C. and Maryland, but also the frequency with which Maryland traffic control officers cited D.C. residents for minor infractions of the law, including not displaying an up-to-date Maryland plate on the first days of the new year. In fact, the Post indicates that the traffic law enforcement issue was greater than the registration fee disparity. "Indignation among Washington automobilists over the treatment accorded them for a long time in Montgomery and Prince Georges counties, Md., is understood to be the main reason for the commissioners [enactment of the January 16 provision]."

December 1923: A Truce is Reached

Through 1923 it was a common sight to see Maryland license plates attached to vehicles based (and registered) in the District of Columbia. In fact, due to the small size of D.C. and the numerous nearby commercial centers of Maryland, it was unusual to see a D.C.-plated vehicles that did not also have a Maryland plate. It all changed for 1924, the first year in which motorists of each jurisdiction were allowed to travel into the other with only their home-jurisdiction registration and plates.

Through 1923 it was a common sight to see Maryland license plates attached to vehicles based (and registered) in the District of Columbia. In fact, due to the small size of D.C. and the numerous nearby commercial centers of Maryland, it was unusual to see a D.C.-plated vehicles that did not also have a Maryland plate. It all changed for 1924, the first year in which motorists of each jurisdiction were allowed to travel into the other with only their home-jurisdiction registration and plates.

Although the relationship between a gasoline tax being enacted in Washington and vehicle registration reciprocity between Maryland and D.C. is unknown, passage of a gas tax bill expected to be presented to Congress late in 1923 was cited by a March 1923 Frederick (Md.) Post article as crucial to bringing about reciprocity. The possibility that a decision on the bill might not be made until early 1924 caused Maryland officials to consider extending the life of 1923 registrations and license plates. "Purchase by District autoists of Maryland license tags for 1924 need not be made at the beginning of the new year, but can be deferred even as late as February, if the Maryland state highway commission can receive definite assurance in December that the 2-cent gasoline tax bill designed to bring about reciprocity in license tags between the District and Maryland will pass Congress shortly after it reconvenes," reported the Post.

Although the relationship between a gasoline tax being enacted in Washington and vehicle registration reciprocity between Maryland and D.C. is unknown, passage of a gas tax bill expected to be presented to Congress late in 1923 was cited by a March 1923 Frederick (Md.) Post article as crucial to bringing about reciprocity. The possibility that a decision on the bill might not be made until early 1924 caused Maryland officials to consider extending the life of 1923 registrations and license plates. "Purchase by District autoists of Maryland license tags for 1924 need not be made at the beginning of the new year, but can be deferred even as late as February, if the Maryland state highway commission can receive definite assurance in December that the 2-cent gasoline tax bill designed to bring about reciprocity in license tags between the District and Maryland will pass Congress shortly after it reconvenes," reported the Post.

In fact, as the end of 1923 neared officials of the two jurisdictions convened and reached a provisional reciprocity agreement, one that shortly became permanent, in spite of the gas tax issue not yet having been settled. Constructive communication about the nagging issue was apparently conducted between Maryland governor Albert C. Ritchie and the D.C. commissioners during 1923, and by this time both sides seemed motivated to reach an agreement. "When it became apparent that Congress could not be made to move so quickly," wrote the Frederick Post in early December, three days after the 68th Congress convened on Dec. 3, "and there seemed to be some danger that reciprocity could not be accomplished by the first of the year, the commissioners of the District suggested that Maryland and the District declare a truce during January and February, and that each honor the others licenses pending Congressional action." Presumably that action was forthcoming, effectively ending the era of multiple-plated cars in the capital region.

|

This page last updated on December 31, 2017 |

|

|

copyright 2006-2018 Eastern Seaboard Press Information and images on this Web site may not be copied or reproduced in any manner without consent of the owner. For information, send an e-mail to admin@DCplates.net |