The Assignment of 1958 Reserved Registration Numbers

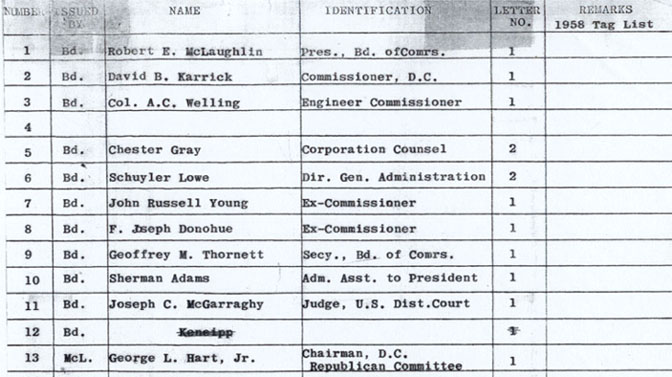

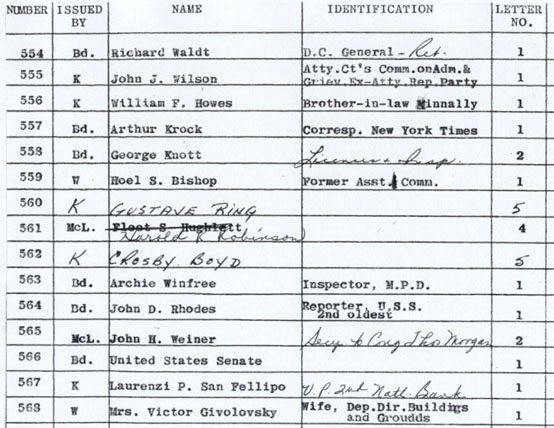

Preserved in the National Archives is a 51-page typewritten document entitled "1958 Tag List" that appears to be the record of registration assignees maintained by the office from which numbers 1 through 1200 were assigned. We have entered this complete ledger into a spreadsheet so that the data may be sorted by plate number, name, and other parameters. Although lists of low plate assignees were routinely published in Washington newspapers during the 1960s and 1970s, the 1958 list is particularly noteworthy because in many cases there is an indication as to the assignee's position in the community that warranted this honor, as well as a notation as to which of the three commissioners assigned the number. The three-member D.C. Board of Commissioners during 1958 was comprised of Robert E. McLaughlin, its president; David B. Karrick; and Col. Alvin C. Welling, the Engineer Commissioner.

In analyzing the 1958 data we have filled in missing data only in the relatively small number of instances in which we believe our assumptions are reasonable. For example, the list indicates that the assignee of registration no. 1092, H. Loy Anderson, is the president of Congressional Country Club, and that the assignment was made by Commissioner Robert McLaughlin. Number 742 was also assigned by Commr. McLaughlin to someone named H. Loy Anderson. Due to the similarities and unusual name, we've assumed that both numbers were assigned to the same person and therefore consider him a multiple-plate assignee even though there is no indication as to whether the Mr. Anderson to which 742 was assigned was president of Congressional Country Club.

Although mostly typewritten and therefore permanent, the list does include a few manual entries and corrections, some more interesting and relevant than others. For example, number 12 was unassigned according to the list, but typed in the line for that number and then crossed out is "Keneipp" (as pictured below). Presumably this is evidence of this number having initially been intended for George E. Keneipp, who is known to have served as director of the city government's Dept. of Vehicles & Traffic (its DMV) at least during the early 1950s, if not longer. When Mr. Keneipp died is unknown, but 1958 reg. no. 418 is listed as having been assigned to Ruth R. Keneipp, "Widow - George, Dir. of V&T," and the appearance of this entry in the list is inconsistent with others, suggesting that it was not made simultaneously with most others. It is therefore reasonable to assume that no. 12 had been intended for Mr. Keneipp, and 418 for someone other than Ms. Keneipp, but that he died early in calendar year 1958, after the initial assignment of 12 had been made but before the registration and plates had been issued, and that instead of providing 12 to his widow, she was given 418. Number 1136 was assigned to George E. Keneipp, Jr., more evidence that when the holder of a plate died the number was not passed on to an heir, but rather taken back for issuance to someone else.

There are few names on the 1958 list that today we might still consider noteworthy:

-

37: Patrick A. O'Boyle, Archbishop of Washington, 1948-1973

-

71: William Brennan, Jr., Supreme Court Justice, 1956-1990;

-

98: J. Edgar Hoover, first director of the FBI, 1935-1972;

-

145: Dean Acheson, Secretary of State in the Truman administration;

-

189: Calvin Griffith, president and owner of the Washington Senators baseball team;

-

230: J. Willard Marriott, founder of the hospitality empire that today bears his name, although at the time it was named Hot Shoppes;

-

312: Edith Bolling Wilson, former first lady;

-

416: George P. Marshall, president and owner of the Washington Redskins football team

-

587: Douglas McArthur II, nephew of Gen. Douglas McArthur and a career diplomat who served as ambassador to Japan, Belgium, Austria, and Iran;

-

599: William O. Douglas, Supreme Court Justice, 1939-1975;

-

626: Jacqueline Bouvier Kennedy, wife of future president and then Senator John Kennedy;

-

839: John Sirica, Judge, U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia, who presided over the the trial of the Watergate burglars in late 1972 and early 1973, and later ordered Pres. Nixon to turn over his recordings of White House conversations

Anna C. Buettner, the D.C. Dept. of Vehicles & Traffic employee most responsible for the organization and distribution of vehicle license plates, used registration number 38 in 1958. Only two numbers appear to have been assigned to the executive branch of the federal government for use on leased Cadillacs for members of the administration: no. 111 was a fixture on the vice president's limousine, and no. 117 was on the limousine of the attorney general. White House press secretary James Hagerty had numbers 116 and 270.

Commissioners Carefully Protected the Lowest D.C. Registrations

We have no direct evidence as to the methodology of how the 1,200 lowest 1958 registration numbers were divided among the three commissioners for assignment to family members, friends, business associates, and constituents. However, a March 1953 memo to director of vehicles and traffic George F. Keneipp from then commissioners F. Joseph Donohue, Renah F. Camalier, and Louis W. Prentiss not only provides information about this annual task but also illustrates how much control the three exerted over the use of the then 1,000 coveted low registrations. Throughout the seven-paragraph document the commissioners repeat, in varied but always forceful directives, that they and only they would dictate how the plates would be assigned, and that the director of vehicles and traffic should not even think about promising a plate numbered below 1001 to anyone. At the time, the director had control of numbers 1001-9999 as well as plates with a single letter followed by one or two numbers. However, correspondence from 1949 indicates that for that year and 1948 the commissioners also provided to him ten numbers from their pool of 1-1000 to distribute. The director asked for more than ten for 1949 but his request was denied, and apparently he didn't even receive the same numbers in the two consecutive years. In the brief Feb. 8, 1949, memo in which the commissioners announced their decision to not provide the director with more than ten numbers for the registration year that would begin in less than two months, they added “You will be notified at a later date as to the particular numbers assigned to you.” For how long after 1949 the director of vehicles and traffic was provided with plates from the population carefully protected by the commissioners is unknown.

In their March 5, 1953, memo the commissioners summarized for Mr. Keneipp proceedings of a Board meeting held that day (at which he was present) that included a discussion of how low numbers for the 1953 registration year would be distributed among themselves and, in turn, assigned to motorists. First, Commr. Donohue, the Board's president, announced that the commissioners collectively “have designated certain tags to be issued by the Board as a body. The three special assistants to the Commissioners will prepare a list designating these 'Board Tags' and the persons to whom they are to be issued. They will send a copy of this list to the Director of Vehicles and Traffic for processing the tags.” Presumably this was not a new process, but rather consistent with how it had occurred in previous years. As shown below, 40% of low plates assigned in 1958 were Board Tags.

The remaining numbers were divided among the three commissioners “to issue as he desires,” although how non-Board numbers were allotted to each is unspecified. Each commissioner was to provide his list of assignments to Mr. Keneipp, “who will issue the tags only to the prescribed individuals.” The director was to notify the commissioners of instances in which more than one number was assigned to an individual, and each of the commissioners also provided his list to his two colleagues for their review as an additional measure designed to prevent the assignment of multiple plates to individuals thought to not be worthy of such a distinction. Every Friday during the period that plates were being distributed, the director was to provide to each commissioner (through his special assistant) a list of numbers from his list, as well as Board Tags, that had been issued that week.

As mentioned, the March 5 memo includes multiple warnings to the director that he not assign numbers provided to the commissioners. In fact, the fourth paragraph is devoted entirely to the subject: “Each Commissioner will authorize the Director of Vehicles and Traffic, through his Special Assistant, to issue only those tags on his particular list. Under no condition will any tag from 1 - 1000 series be issued without prior approval of the Commissioner concerned. Issues subsequent to the initial list will be made only upon written authority of the proper Commissioner or of his Special Assistant.”

The commissioners also made it clear that inquiries about low plates received by mail were to be promptly acknowledged by the director, then forwarded to the Board president “for consideration and appropriate action.” “All external correspondence on this subject, including any letters covering transmittal of tags, will make clear reference to the fact that these tags are issued by the direct authority of the Commissioners and by no other agency or person of the D.C. Government.” Evidence that this directive was followed may be seen on a separate page.

The commissioners ended their memo with this reminder: “The Director of Vehicles and Traffic will assure that no 1 - 1000 tags are issued except when properly prescribed.” Based upon the tone of their instructions, one can only imagine what unpleasantness would have befallen Mr. Keneipp were he to ever have allowed a plate numbered below 1001 to be issued to anyone not approved by Mr. Donohue, Mr. Camalier, or Mr. Prentiss.

Composition of The 1958 List

There are ten numbers with no associated assignee data on the 1958 list: 4, 12, 44, 177, 191, 249, 367, 380, 630, and 808. Note that in most cases in our analysis documented below the total number of registrations is 1,190, not 1,200, due to these ten numbers having no data. It was only for three years, 1957-1959, that 1,200 reserved registration numbers were assigned. Prior to 1957 there were 1,000, and for 1960 the quantity was increased to its present level, 1,250.

The second column on the list, entitled "Issued By," features one of four notations. "Bd." indicates a "Board Tag" as defined above, and the others indicate which of the three commissioners assigned the number. The composition of the 1958 list by assignor notation is as follows::

Notation |

Assignor |

Qty. |

|

Bd. |

the Board of Commissioners collectively | 478 |

40.2% |

McL. |

Commissioner McLaughlin | 311 |

26.1% |

K |

Commissioner Karrick | 180 |

15.1% |

W |

Commissioner Welling | 221 |

18.6% |

| sub-total, assigned by one of the commissioners | 712 |

59.8% |

|

| total registration numbers assigned | 1,190 |

100.0% |

Sixty percent of the available numbers were therefore assigned by the commissioners, with the remaining 40% allocated by the Board collectively or based upon a perpetual arrangement of some sort. It is also possible that the Board category includes numbers provided to others to assign, although this seems doubtful because had this occurred a distinctive notation would likely have been used in the list.

Although data that appears in the "Name" column is usually an individual's name, in some cases it is the name of a business or government institution. This is our summary of how the numbers were assigned based upon data in the Name column:

Assignee Type |

Qty. |

|

| Husband and wife | 9 |

0.8% |

| Men | 914 |

76.8% |

| Women | 167 |

14.0% |

| sub-total, individuals | 1,090 |

91.6% |

| Businesses | 76 |

6.4% |

| Government agencies | 24 |

2.0% |

| total registration numbers assigned | 1,190 |

100.0% |

The purpose of the "Letter" column is unknown, but numbers shown therein are believed to reference standard notification letters sent to assignees depending on whether for 1958 they were receiving a reserved number for the first time, a number different than what they had for 1957, or the same number that they had in 1957. Undoubtedly there were other less common scenarios that required customized or personal correspondence.

Dissecting The 1958 List

As indicated previously, most intriguing about this list compared to those published in later years is that with this document we have personal information about many of the assignees, allowing us to know (or at least speculate) why they were able to use one or more of the District's 1,200 lowest, most distinctive registration numbers. To try to form a picture of the preferred 1,200, we created a list of seven main categories and placed every assignee within one of them. More specifically, our list is comprised of 32 classifications (departments and boards) within the D.C. government category; 18 classifications relating to the federal government; each branch of the U.S. military; ten classifications for members of the judiciary and those related to the court system; many classifications for businesses; and several for political parties, unions, educational institutions, and other types of not-for-profit organizations. Here is a list of how the 1,190 assignees fell into our categories:

Assignee Category |

Qty. |

|

| District of Columbia Government | 289 |

24.3% |

| United States Government | 128 |

10.8% |

| Unspecified government agencies | 12 |

1.0% |

| United States Military | 67 |

5.6% |

| Judiciary and Court System | 89 |

7.5% |

| Businesses | 305 |

25.6% |

| Organizations | 54 |

4.5% |

| sub-total, categorized assignees | 944 |

79.3% |

| Uncategorized assignees | 246 |

20.7% |

| total registration numbers assigned | 1,190 |

100.0% |

Unfortunately, descriptions in the "Identification" column of the list are often unclear or nonexistent, resulting in more than 200 assignees being placed in an uncategorized classification. It is certain that every one of the 1,190 registrations was issued for a specific reason, which is to say that none were distributed over-the-counter to motorists that were indifferent as to their registration number. Undoubtedly at least a few assignees were really not that interested in having a low plate, but if they cared enough to respond to the assignment letter heralding their good fortune and to appear at the District building to collect their plates, they are included in the list. In other words, all of the 246 uncategorized assignees could be placed in one of the categories were we to know something about them.

Each of the categories listed in the table above except "Unspecified government agencies" and "Uncategorized assignees" includes a catch-all classification in which is placed individuals, businesses, and government agencies of a miscellaneous nature, as well as those for which the proper classification within a category is unclear. Here are some examples of identifications that caused individuals to be placed in the miscellaneous classification within the D.C. Government category:

-

Undertaker's Committee

-

Widow, Supt. Trees and Landscaping

-

D.C. Govt. retired

-

Wage Board

-

Supt. D.C. General (ret.)

-

Chrm. Cit. Welcoming Comm., Westinghouse Distributor

Not previously defined is our Unspecified Government Agencies category. An example of the twelve people placed here is the gentleman to whom plate number 352 pictured at the top of this page was assigned. His identification in the list is "Deputy Dir., Occ. & Profs." We are inclined to assume that "Occ. & Profs." was a D.C. government agency that registered and monitored practitioners of various occupations and professions. However, with no direct evidence as to whether "Occ. & Profs." is a federal or city agency, he wound up in the "unspecified" category until further research determines definitively where he should be placed.

Each assignee has been placed in only a single classification even though many could appear in more than one. For example, if we knew how many individuals on the list were attorneys and placed them in our "Businesses - Law" classification before any other, it would have the most entries because so many assignees are lawyers. However, because some of the attorneys identified in the list are also government employees or served on various city boards and committees, they usually didn't make it into the law classification. The 36 people included therein, in fact, are mostly those for which the identification was listed only as "attorney."

On the other hand, we placed in various classifications people that in their daily life were only minimally associated with it. For example, plate no. 600 was issued to Commr. Karrick's sister-in-law, so she is included in the Commissioner's classification simply because our purpose was to identify relationships that resulted in someone getting one of the preferred plates, and we know nothing else about her to cause us to place her anywhere else. If we learned that she worked for the city or federal government, for example, then we would have to decide which classification was more relevant to this analysis.

Despite the various limitations of the list, it is still an interesting snapshot of who was afforded the opportunity to use one of the District's numbers-only license plates for 1958. Remembering that about 21% of the assignees could not be placed in any classification, it is still relevant to examine which ones include the most assignees. Here is a list of those classifications with at least 15 associations, followed by a discussion of each one:

Assignee Classification |

Qty. |

| U.S. Army | 41 |

| Commissioners, former commissioners, staff | 38 |

| Metropolitan Police | 38 |

| Attorneys | 36 |

| Bankers | 30 |

| U.S. Senate | 28 |

| Print media | 25 |

| U.S. District Court | 24 |

| Physicians | 23 |

| Municipal Court | 22 |

| U.S. House of Representatives | 19 |

| D.C. Traffic Advisory Board | 18 |

| U.S. Supreme Court | 15 |

| Motor vehicle businesses | 15 |

Not surprisingly, the list of reserved number assignees is dominated by government workers, lawyers, bankers, and community members with an association with the automobile. If you weren't a judge, D.C. government employee, lawyer, or banker, qualifying in more than one of our classifications, such as being an auto dealer and serving on the Traffic Advisory Board, Citizens Advisory Council, or even the Boxing Commission was definitely a plus. Of the 90 available two-digit numbers, 35 (39%) were assigned to judges, associate justices, and others placed in our Judiciary classification. No other classification or category, not even D.C. government employees as a group, comes close to this coverage at the low end of the registration number spectrum.

U.S. Army The Army is the most represented classification in the list, and it far outpaces the other military branches when it comes to interest in reserved-number plates. Forty-one individuals associated with the Army were identified in the 1958 list, including 15 with the rank of Major General and nine Colonels. In contrast to the Army, only 13 assignees are in or related to the Navy, and only a single assignee associated with each of the Air Force and Marines are identified. There are 11 individuals with military titles whose military branch are unspecified, and the five high-ranking Defense Dept. officials on the list are placed in a separate classification within the U.S. Government category.

Commissioners The then current commissioners used several plates for themselves, and many other plates are associated with them, such as 840, assigned to Ms. Juliet Pothier, identified only as a friend of Commr. McLaughlin. Undoubtedly many of the almost 250 anonymous, uncategorized individuals on the list received their plates because they were acquainted with one of the commissioners. According to the list, however, Commr. McLaughlin had only plate no. 1, Commr. Karrick used plates 2 and 87, and Commr. Welling only no. 3. Numbers 975, 949, and 915 were Board-assigned numbers associated with individuals that worked within each commissioner's office. The Board's secretary, Geoffrey Thornett, used plate no. 9.

Many former commissioners maintained prominent places in the list, most notably relatives of Renah F. Camalier, an attorney who served as Commissioner in the mid-1950s. His wife used no. 100 in 1958, his brother 498, and a law partner 364, among others. Other low numbers associated with former commissioners in 1958 include 8, 14, 22, 31, and 66.

Metropolitan Police No section of the D.C. Government is better represented in the 1958 list than the police department, presumably at least in part because it was among the largest city agencies in terms of personnel. Among the 38 numbers associated with the police dept. in our list is 85, assigned to former Chief Ernest Brown. In only one instance does the list indicate that a number (1185) matched an officer's badge number, but there are probably multiple undocumented instances of this relationship. It is worth noting that all but four of the numbers in this category are attributed to the Board, not one of the commissioners.

Attorneys It is not unreasonable to assume that more than 150 of the 1958 assignees were attorneys, but many identified in the list as practicing this profession were placed in other classifications because another role was felt to be more of a factor in their being granted a reserved-number registration. Most of the 36 men in this category are identified only as an attorney in the list. The lowest numbers are 25, assigned to Douglas Whitlock; and 88, assigned to Ralph Becker, both provided by Commr. McLaughlin. Neither gentleman had another low number.

Bankers A few Washington banks were apparently fairly plate-conscious places to work in 1958, most notably Riggs Bank, the president of which had three plates (as discussed below). A stenographer and Republican party worker, Florence Coulson, had no. 224, and Riggs cashier Newton B. Warwick used 484. American Security & Trust is associated with four plates, including 95 and 987 used by its president, Daniel Bell, and Lincoln Bank appears on the 1958 list three times. Number 400 was assigned to Bruce Baird, president of National Savings & Trust.

U.S. Senate Although some of the plates included in our Senate classification were used by senators and their relatives, such as 626 assigned to Jacqueline Bouvier Kennedy, others were associated with institutions within the Senate itself. Number 55 was assigned to the Majority Leader regardless of who filled that role at any particular time, and 81 was the President Pro Tem plate. Other numbers assigned simply to the Senate were 157, 161, 167, 566, and 829. Clinton P. Anderson, a senator from New Mexico and former Secretary of Agriculture, used no. 24, and no. 112 was assigned to Sen. Mike Monroney, of Oklahoma.

Print Media News companies from around the world had correspondents stationed in Washington, and some of them were prominent enough to be granted reserved-number plates in 1958. No. 151 was assigned to the Tribune Co. of Chicago; 557 to a New York Times reporter; and 957 to a photographer for the Pittsburgh Courier. Of course, representatives of local institutions such as the Post, News, and Star are well represented on the list, too. Eugene Meyer, who was chairman of the Federal Reserve from 1930-1933 and publisher of the Washington Post upon his purchase of the paper in 1933, had no. 149 in 1958. Ben Gilbert, then City Editor of the Post, used no. 490. Evening Star president Samuel Kaufmann had plate no. 56, and editor Ben McKelway had no. 58. Washington News editor John O'Rourke was assigned no. 60. Bill Hutchinson, a Washington fixture since moving to D.C. in 1920 to work for William Randolph Hearst's International New Service, of which he was the head by 1958, had no. 53 for 1958. He died on May 25, at age 62, less than two months into the registration year.

U.S. District Court Judges and Associate Justices of numerous courts are included on the 1958 list, and the U.S. District Court is prominently represented by many judges, former judges, and their wives. Their clout with the commissioners is indicated by the fact that of the 24 assignees in this category, an amazing 17 had two-digit numbers. All but three of the numbers, those being three-digit combinations assigned by Commr. McLaughlin, are Board-designated numbers.

Physicians There is nothing particularly noteworthy about the group of physicians identified in the 1958 list. None have more than a single number, and their numbers are not particularly low, the lowest of the 23 being 143, 152, and 267.

Municipal Court judges and their family members, like their District Court brethren, generally have low numbers. Of the 22, six have two-digit numbers (the lowest being 21) and 13 have three-digit combinations, five of those being between 100 and 150. Three assignees in this category have numbers above 1000.

U.S. House of Representatives Five of the 19 numbers in this classification are assigned to the institution itself, not to individuals, among the honored offices being the House Speaker with no. 18, and those of the Majority and Minority leaders with 294 and 350, respectively. William McLeod, clerk of the House District Commission, received no. 40, with the remaining House numbers being of the three-digit variety.

D.C. Traffic Advisory Board Of the city government's several boards, commissions, and councils, this one had the most low-number assignees. Two numbers were below 100, the remainder being between 255 and 845. Jack Blank, owner of Blank Pontiac, used no. 77 in 1958.

U.S. Supreme Court justices and their spouses have consistently received low numbers, and certain numbers appear to have been passed from one justice to another over the years as they joined and left the high court. No. 50 has historically been reserved for the Chief Justice's car. We identified 15 numbers associated with the Supreme Court in 1958, with eight being between 47 and 86; six being three-digit combinations, and one being a four-digit number assigned to a deputy clerk of the court. All of the lowest numbers in this classification were assigned by the Board collectively, not by individual commissioners.

Motor Vehicle Businesses It's not surprising that individuals and businesses in the auto industry appear on the low-number assignee list. Capitol Cadillac is most prominent, as discussed below, but there are others, such as no. 358 with Arcade Pontiac, 547 with Red's Kaiser-Frazer, 571 with Jack Blank Pontiac, and 672 with Ourisman Chevrolet. General Motors Corp. had 737, and Chrysler Corp. had 1010. For furnishing a car for use in driver training, presumably to the public school system, the Board rewarded auto dealer Stanley Horner with registration no. 238.

There were many D.C. vehicle owners that were important enough to warrant more than one of the coveted 1,200 lowest plates. Not surprisingly, the commissioners themselves are in this category. For 1958, Commissioner Karrick appears to have been most generous to his relatives and friends when assigning low plates.

Individuals With More Than A Single Number There are a surprising number of individuals to whom more than a single number were assigned or associated, separate from "family plates" discussed below. Leading the pack with three numbers are Riggs Bank president Robert V. Fleming, and L. Corrin Strong, a former ambassador to Norway.

Mr. Fleming became president of Riggs Bank in 1925, at age 35. For most of its 169-year existence Riggs was the largest bank in Washington, and it was often referred to as the "Bank of Presidents" because by the time in was acquired by PNC Financial Services in 2005, 23 chief executives or their family members had been among its depositors, along with many congressmen, high-ranking military officials, and other prominent figures. Mr. Fleming became a trusted advisor to several presidents, most notably Franklin D. Roosevelt, Harry S Truman, and Dwight D. Eisenhower. He served as chairman of the Pres. Eisenhower's 1957 inaugural committee, and his inaugural plates and registration card for that year may be seen here. As for 1958 auto registrations, he had numbers 26 and 440, with the third associated directly with him being 276, assigned to the bank for use on "Bob Fleming's car." The lowest plate was a Board-assigned number whereas the others were assigned by Commr. Welling.

As for Mr. Strong, he was assigned numbers 129, 339, and 682. The first two were provided by Commr. McLaughlin, and the highest by Commr. Karrick.

We counted 25 individuals with two numbers, with Commr. Karrick leading the pack with nos. 2 and 87. Capt. Frank Lovelace is the only one of the 25 to have consecutive numbers, Commr. McLaughlin having provided 1107 and 1108 to him. Only one woman had two directly-assigned numbers, that being Anna K. Beahan, of the D.C. Republican Women. Her status resulted in Commr. Karrick providing 791, and 1028 was assigned by Commr. McLaughlin. Two-plate assignees whose holdings included a two-digit number were:

-

14 and 266: Samuel Spencer, a former commissioner; both numbers assigned by Commr. McLaughlin;

-

22 and 485: Maj. Gen. Louis Prentiss, a former engineer commissioner; the lower number was a Board issue and the higher was assigned by the current engineer commissioner, Col. Welling;

-

27 and 371: George E.C. Hayes, Commissioner of the D.C. Public Utilities Commission; the lower number was a Board issue and the higher was assigned by Commr. McLaughlin;

-

28 and 392: Clyde Garrett, an attorney and D.C. representative to the Republican National Committee; both numbers were assigned by Commr. Karrick;

-

45 and 805: David Bazelon, a Court of Appeals judge; both numbers are attributed collectively to the Board;

-

75 and 690: Wiley Buchanan, Chief of Protocol for the U.S. State Dept.; the lower number was a Board issue and the higher was assigned by Commr. McLaughlin;

-

83 and 699: Geneva Barkley, a builder; the numbers having been assigned by Commrs. Welling and McLaughlin, respectively;

-

93 and 119: Edgar Morris, a Westinghouse distributor; the lower number was a Board issue and the higher was assigned by Commr. McLaughlin; and

-

95 and 987: Daniel Bell, president of American Security and Trust; both numbers are attributed collectively to the Board.

All In The Family There are undoubtedly some familial and family/business relationships that are not evident in the 1958 list due to a lack of detail. However, here are a few noteworthy ones we've identified.

Commr. Karrick seems to have been especially adept at assigning plates to family members. He kept 2 and 87 for himself, provided 138 to his brother James, and 600 to his sister-in law Marian. His secretary, Dorothy Allen, used 235, and an office employee, William Johnson, had 949. Mr. Karrick's cousin, E.K. Morris, motored around Washington with plate 360.

Plates 70 and 445 were assigned to the Kane Transfer Co. and used by its president, Francis J. Kane, and his wife, respectively. Their daughter, Gertrude Kane Forbes, had number 748, and Jim Castiglia, a son-in-law, had no. 193 in the name of Redskin Van Service.

There are lots of Websters in the 1958 list, but whether any of them are related to any of the others is unknown. John G. Webster received no. 431 from Commr. Welling, and numbers 861 and 1057 were registered in the name of John G. Webster, Co., and were assigned by Commrs. Karrick and McLaughlin, respectively.

Capitol Cadillac is believed to have been the local dealer that provided official cars to the federal and city governments, and its owners and key employees all seem to have had low-number plates. Company president Floyd Akers, who also served on the city's Police Complaint Board, had number 90, assigned collectively by the Board, and Commr. Karrick arranged for his wife Irma to have no. 535. Number 154 was assigned to the company and apparently used by its secretary, and 657 was on the car (likely a shiny, new 1958 Cadillac) of Hilleary C. Hoskinson, the agency's sales manager.

George L. Hart, Sr., a reporter who covered Republican National Conventions from 1916 through 1952, received nos. 163 and 758 from Commr. Karrick. His son, George L. Hart, Jr., chairman of the D.C. Republican Committee, received plate no. 13 from Commr. McLaughlin, and daughter Catherine Hart Brent used no. 389 courtesy of Commr. Karrick.

There are numerous examples two low numbers being in the same family between husband and wife, father and son, etc. Perhaps most noteworthy are the brothers McGarrahy. Joseph, a U.S. District Court judge, had number 11, and his brother, Alfred, managed Scholl's Cafeteria and used no. 97. Another District Court judge, John Sirica, had plate no. 839, and his wife Lucille used no. 332, both provided by Commr. McLaughlin.

Ten Years Later: Reserved Plates in 1968

The roster of reserved registration assignees is often characterized as a form of social register of Washington. One's public fortunes can be monitored, to a certain extent, by whether they move up or down on, or appear on or are removed from, the list every spring. This perception was heightened during years of the 1960s and 1970s when the list was published annually in at least one local newspaper. Indeed, the brief introduction to the published 1968 list discussed here ends with this suggestion: The Washington Daily News suggests tag-watchers clip this list and keep it in the glove compartment for handy reference."

Unfortunately, the 1968 list published by the News on June 11, 1968, a few months after the dust had settled on 1968 assignments, is not comparable to our 1958 internal (i.e. non-published) list because assignee information is omitted for 201 (16.1%) of the 1,250 available numbers. It is almost certain that all of these numbers were issued, but that the data was omitted from publication at the request of the assignee or for some other reason. For example, although no. 50 is marked "not issued," we know that that number had historically been reserved for the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, and likely was for 1968, as well.

One characteristic of Washington that makes comparing 1958 to 1968 interesting is that a change in the form of government that occurred in the intervening years undoubtedly had a direct impact on the assignment of low-number registrations. In 1967, the century-old system under which the District's affairs were managed by a three-member Board of Commissioners was replaced with an appointed mayor and city council. This interim structure gave way to the 1973 Home Rule Act, which ushered in the present form of elected mayor and council in 1975. For 1968, however, plates were presumably assigned by Mayor Walter E. Washington, with the assistance of members of his staff who knew the history of particular numbers and assignees.

One characteristic of Washington that makes comparing 1958 to 1968 interesting is that a change in the form of government that occurred in the intervening years undoubtedly had a direct impact on the assignment of low-number registrations. In 1967, the century-old system under which the District's affairs were managed by a three-member Board of Commissioners was replaced with an appointed mayor and city council. This interim structure gave way to the 1973 Home Rule Act, which ushered in the present form of elected mayor and council in 1975. For 1968, however, plates were presumably assigned by Mayor Walter E. Washington, with the assistance of members of his staff who knew the history of particular numbers and assignees.

In comparing lists of 1958 and 1968 registrations 1 through 100, we find no data for three numbers (4, 12, and 44) in the earlier list, and fourteen (4, 6, 7, 34, 40, 41, 50, 53, 65, 78, 84, 93, 96, and 98) in the later one. Thirty-five of the first 100 numbers for which data is present for both years are assigned to the same person or company in 1958 and 1968. Of the 35 judges and individuals associated with the court system that had two-digit numbers in 1958, 20 still had them in 1968, 10 had been reassigned, and 5 were "not issued" according to the 1968 list.

Prior to 1967, registrations 1, 2, and 3 were traditionally assigned to the commissioners, with 1 going to the Board's president and 3 to the engineer commissioner. In 1968, 1 was assigned, not surprisingly, to the appointed mayor, and numbers 2 and 3 were used by the city council chairman and deputy mayor, respectively. Although the names of Walter Washington and his wife do not appear on the 1958 list, for 1968 he was no. 1 and she 67.

There is not a single individual with the surname of Fauntroy on the 1958 list, yet by 1968 there were no less than five. Walter E. Fauntroy, a D.C. native, pastor and civil rights leader, was a member of the new city council in 1968, and although his name does not appear on the list, we believe he likely had one of the lowest numbers marked "not issued" in 1968, possibly 4, 6, or 7, so influential was he in D.C. public administration at the time. He went on to represent D.C. in the House of Representatives for 21 years, from 1971 to 1991. His wife, Dorothy, had no. 87 in 1968, and two brothers used 172 and 314. Whether other Fauntroys in the 1968 list are relatives to the councilman is unclear.

Just as members of the judiciary occupy prominent positions in the 1958 list, so too do they feature prominently ten years later, although several active judges in 1958 have "(ret.)" adjacent to their 1968 list entry. Supreme Court Justice William O. Douglas moved up from 599 in 1958 to 31 in 1968. Similarly, Judge John Sirica moved up from 839 to 126 over the ten-year span, while his wife remained, apparently content, at 332. By 1968, Justice Thurgood Marshall was using no. 72, whereas ten years earlier that number was assigned to Marion Frankfurter, wife of Supreme Court justice Felix Frankfurter, who served on the high court until 1962 and died in early 1965.

|

This page last updated on December 31, 2017 |

|

|

copyright 2006-2018 Eastern Seaboard Press Information and images on this Web site may not be copied or reproduced in any manner without consent of the owner. For information, send an e-mail to admin@DCplates.net |